Deep Dive: Illiquidity premium key in private equity returns – Blurring the line

In a recent article for Investment Week, SECOR’s Bo Brownlee, CFA, takes a deeper dive into the illiquidity premium in private equity returns.

Private Equity (PE) provides an additional return premium to investors as compensation for holding risky investments over a multi-year time horizon. In contrast, public markets boast deep and active markets that offer the prospect of immediate liquidity. This illiquidity premium has been a key component in the long-term return premium investors have received from private equity. The size of the premium can be debated, but there is nevertheless a strong case for its existence.

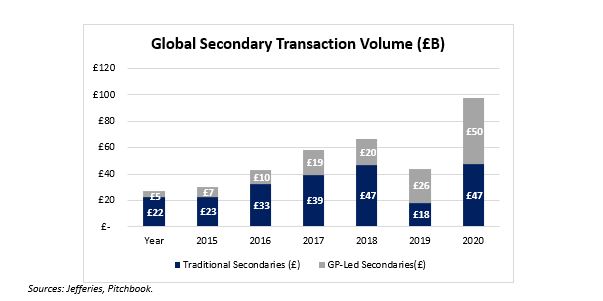

The purpose here is not to argue the appropriate size of the premium, but to take a closer look at a phenomenon in the private equity market that is impacting that premium, specifically the growth in the secondary market for private equity assets. The secondary market allows a new Limited Partner (LP) to buy a fund interest from a current LP. Increasingly, that buyer has been a PE fund dedicated to purchasing stakes in the secondary market. There has been an explosion in secondary transactions supported by these specialist funds that offer an avenue for early liquidity for limited partners.

While rapidly expanding, secondary transactions remain complex, opaque, and require a high level of sophistication and experience to navigate successfully. With recent regulatory forces, such as the DB funding code in the UK and Pensions Reform in the Netherlands, driving divestment of illiquid assets and the maturing profiles of pension scheme liabilities, SECOR sees strong demand for solutions provided by secondaries and are actively working with several clients to reap the rewards and navigate the challenges.

Once a niche market, catering primarily to forced sellers for regulatory reasons or financial distress, the secondary market has become a far more mainstream corner of private equity. Although still representing a small portion of the entire universe, secondary managers increasingly provide an outlet for investors with shortened time horizons.

Adding to growth in these more traditional secondary transactions, there has been a surge in General Partner (GP)-sponsored secondaries. In a GP-led secondary, a fund sponsor arranges for a sale of all or a portion of the assets of an existing managed fund on behalf of the LP’s that are seeking liquidity. The capital providers for these transactions are typically large dedicated secondary funds with the purchased assets frequently placed in a “continuation” fund. This continuation fund is often managed by the same GP as the fund from which they were purchased. This strategy had historically been reserved for troubled funds or those nearing conclusion but has become much more common as PE investors have become increasingly impatient

- General Partner-led secondaries accounted for 52% of total secondary volume activity in 2021 compared to just 17% in 2015, shown below.

The emergence of a more liquid secondary market has impacted fundraising behaviour as well. Although a long bull market in equity assets has no doubt been a big contributor, the availability of a more liquid secondary market, that provides the ability to truncate the life of a fund, has also played a part in contracting the fundraising cycle.

- The average time between funds for a particular sponsor has shrunk from in the US.[1]

Finally, large mutual fund sponsors have become active in purchasing stakes in private companies before their initial public offering, creating yet another potential source of liquidity for sellers of PE assets. This relatively recent evolution in the private markets has helped prolong the private status for many companies that would have otherwise sought a public listing.

There are clear benefits to PE asset owners of having more and deeper sources of potential liquidity. Those benefits may come at a cost, in the form of erosion of the historical premium relative to public markets, blurring the line between public and private equity. While there are certainly many other factors impacting that relationship, it seems logical that the portion of the historical spread driven by an illiquidity premium should contract as private equity assets become increasing liquid.

[1] Source: Pitchbook