Should Cryptocurrencies Be Included in a Multi-Asset Portfolio?

By Ray Iwanowski

September 2021

Executive Summary

- One of the most hotly discussed topics in institutional asset management over the past few years has been whether institutions should consider allocating to cryptocurrencies. Discussions around this topic have become polarizing as “evangelists” make very aggressive claims of outsized returns under the premise that the nascent asset class provides a “once in a generation” opportunity to invest in assets that are truly “revolutionary” and “disruptive” to traditional notions of fiat money and existing financial systems and institutions. There are some high profile and vocal sceptics who argue that these concepts will prove to have little value and warrant no place in an institutional portfolio. Heretofore, most institutions have aligned with the sceptics but that may change fairly rapidly.

- The Investment Strategy Group at Goldman Sachs Asset Management has addressed this question in multiple publications over the past few years and has emphatically argued that cryptocurrencies are inappropriate for their clients’ portfolios. A June 2021 report[1] presented a thoughtful and thorough analysis supporting their argument for a zero allocation to cryptocurrencies with some fair points.

- One section of the piece presents a quantitative strategic asset allocation modelling analysis backed by the limited historical data available on bitcoin. The conclusion of this analysis is that the appropriate allocation to bitcoin should be zero, unless the allocator believes that the forward-looking expected return of bitcoin is extraordinary and much larger than the historical average.

- We identify several issues with assumptions, calibrations and methodologies used in this analysis. Unfortunately, the authors were not fully transparent on the details that drove the analysis, but we speculate on what might have been used and question the logic and intuition of their conclusions.

- We conduct a similar analysis using SECOR’s strategic asset allocation methodology. Calibrating our model to bitcoin’s historical average return, volatilities and correlations and optimizing toward a typical risk target (roughly the risk of a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio), the model allocation to bitcoin is 10-15%. Although bitcoin’s volatility is high, the risk had been well-compensated with return. One other positive attribute of bitcoin that led to its high allocation is a low correlation with other asset classes, particularly with equity. For strategic asset allocation purposes, we would not recommend assuming that bitcoin’s historical run will continue, but even at lower return assumptions, our analysis results in a meaningful non-zero allocation.

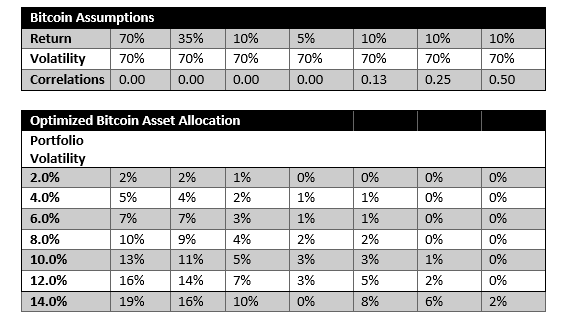

- We clearly recognize the danger in using historical data of an exceptionally performing asset class as the sole input in calibrating an asset allocation exercise going forward. As such, in our analysis, we perform optimizations at various levels of risk tolerances that assume expected returns much lower and correlations much higher than the historical experience. We believe that these assumptions are more appropriate in setting the current asset allocation. Naturally, such adjustments resulted in a much lower allocation to bitcoin than the optimization calibrated to the historical data, but the solution is still non-zero. At certain risk targets, the optimization results in a positive allocation to bitcoin if the expected return is as low as 10% and correlations are as high as 0.25-0.50 – even if bitcoin remains as volatile as the historical experience.

- We also highlight that a different group at Goldman Sachs, the Global Macro Research Team, published a piece in May 2021[2] that outlined their version of a quantitative asset allocation exercise. Their results were more in line with SECOR’s, suggesting an allocation of 5-10% to bitcoin.

Goldman Sachs Perspective

In June 2021, the Investment Strategy Group (ISG) at Goldman Sachs Asset Management (GSAM) released a thorough and well-researched piece entitled Digital Assets: Beauty is not in the Eye of the Beholder. This group has historically been negative on the suitability of cryptocurrencies in client portfolios, stating the following in their January 2018 Outlook (when bitcoin’s price was approximately $15,000):

We also believe that cryptocurrencies have moved beyond bubble levels in financial markets, to levels last seen during the Dutch “tulipmania” between 1634 and early 1637.[3]

In a May 27, 2020 client call (bitcoin’s price was approximately $8,000), the same group presented several critiques of cryptocurrencies and concluded:

We do not recommend bitcoin on a strategic or tactical basis for clients’ investment portfolios even though its volatility might lend itself to momentum-oriented traders.[4]

Despite the significant price run-up of bitcoin (BTC) and other digital assets since those pieces were published, the Goldman Sachs ISG team continued to recommend that investors avoid allocating to cryptocurrencies in their June 2021 publication. In this report, they make some valid points supporting a bearish view on cryptocurrencies. Some of their conceptual arguments for avoiding an allocation to the asset class include:

- Lack of cash flows or earnings

- Limitations as a means of exchange

- Scepticism that cryptocurrencies provide an effective store of value or “digital gold”

- High price volatility

- Regulatory uncertainty

- Concerns about energy usage

- Risks of cyberattacks

For investors considering an allocation to the digital asset space for the first time, Goldman’s extreme negativity provides an important counterbalance to the well-publicized arguments made by crypto bulls active in the financial press, conferences, fund marketing material and on social media.

Although the piece raises generally valid concerns, we believe that there are strong counterarguments to be made that undermine much of Goldman’s thesis that allocations to digital assets are inappropriate for most investors. We will not be outlining the philosophical counterarguments in this note, as there are many well-articulated pieces by experts in the space (Goldman calls them “proselytizers”) who have already addressed these issues[5].

Even if one were to concede all the negative points made above and gave no credence to counterarguments against them, it is rather curious that an asset allocator would then conclude that an allocation to cryptocurrencies is inappropriate at any price. If the investor shares Goldman’s view on the current shortcomings of cryptocurrencies as a means of exchange or as a store of value, they might also envision the adoption of the digital assets in these functions to improve over time. The investor may have a view that such improvement is not reflected in the current price and expects an increase in value when the increased utility for these “use cases” to come to fruition. In this case, they would likely assign a positive and perhaps even high expected return to the digital assets over time.

Some of the negative points listed above reflect the high level of risk that cryptocurrencies carry. Assets that possess high levels of risk on multiple dimensions should not necessarily be excluded from a well-diversified portfolio if they are compensated well enough by a high expected return and sized properly.

We believe it is fair to point out that other asset classes and sectors also warrant similar concerns as those listed above, yet the GS ISG still includes them in an allocation. For example, many growth stocks have low or even negative earnings for the foreseeable future and experience high volatility. Certain sectors such as biotech, small cap and venture capital tend to have many stocks that possess such characteristics. Other sectors and asset classes like utilities, commodities mining stocks, high yield bonds and hedge funds carry significant regulatory, ESG and cybersecurity risks. In such cases, the risks might motivate a down-weighting of such sectors, but these risks should not lead to a zero allocation at all times. It is not clear why cryptocurrencies should be treated differently.

Each investor should take the time to consider both sides of these arguments carefully to determine whether it is appropriate to assign a positive forward-looking expected return to cryptocurrencies and to help assess whether that expected return is high enough to assume the quantifiable and non-quantifiable risks. We believe that Goldman has provided the investment community a valuable service of thoroughly outlining valid concerns in an environment where much of the public discussions tend to be dominated by “evangelists” and “maximalists”. Given the strength of the arguments on both sides, there is not an obviously “correct” view on the forward-looking expected return on these assets, particularly at the current price levels.

Critique of GS ISG Strategic Asset Allocation Analysis

Although much of ISG’s conceptual case against cryptocurrencies is reasonable, we believe that the section of the June 2021 piece entitled “Strategic Asset Allocation Analysis” has serious flaws and warrants further discussion. Specifically, the authors describe a quantitative asset allocation model that uses available historical data and concludes that “the risk, return and uncertainty characteristics of Bitcoin based on our multi-factor model do not support an allocation to Bitcoin”.

Prior to presenting the results of their model exercise, the piece appropriately described some challenges of using historical data on cryptocurrencies in any quantitative analysis, given the limited history, poor quality and potential regime shifts in the statistical distribution of these assets over time due to fundamental changes in the nature/maturity of their markets. It should be noted that these caveats, although particularly relevant to cryptocurrencies, can and should be made about many of the other asset classes that might be included in a strategic asset allocation framework. In some asset classes that are typically considered — such as private equity and hedge funds — the issues may be just as pronounced as in cryptocurrencies.

In evaluating the historical data, GS ISG considered only bitcoin since it has the longest and most reliable history of data. The piece also notes that bitcoin volatility shifted downward starting in January 2014, reporting a realized volatility of 125% pre-January 2014 and 68% post-January 2014. The authors also mention that a Hidden Markov Model indicated that there was a regime shift in volatility around that date. For this reason, they only use data since 2014. We agree that these modelling choices are sensible and reasonable.

In Exhibit 18, the report states that bitcoin has realized an annualized return of 69% since January 2014 and references statistics labelled as “Model-Based Estimates”. Since these statistics are likely the key inputs to their “robust optimization” that yielded a zero allocation to bitcoin, they certainly should have been accompanied by more description of how they were calculated and why they differ so significantly from the historical data.

Some specific issues and questions that we have on the estimates, assumptions and reported results used in the analysis include:

- The “model based” estimate for bitcoin volatility is 93%, despite the reported realized volatility of 68% since 2014. This is not necessarily invalid on its face, as many asset allocation optimization models do not use the full sample realized volatility as the input volatility estimate of an asset or asset class. These models often use a conditional volatility estimate that may differ from the full sample historical estimate, perhaps because the conditional estimate may weigh recent observations more highly that past observations. The estimate may also incorporate some real time information such as the current implied volatility of options. However, the GS authors should have described the methodology used, particularly since there was such a big difference between their estimate and the calculation from historical data.

- Although volatility is an important input to portfolio optimizations, it generally drives the sizing of the allocation rather than whether there will be an allocation at all. Expected returns and correlations are the key drivers of whether an asset or asset class should receive an allocation. Therefore, one of the most relevant statistics presented by GS ISG in this analysis is their estimate of “Risk Premium”, which they reported to be 1.9%. They also point out that there is a fair amount of uncertainty around this estimate and report a one standard error range from -35.2% to 39.1%.

The piece contains no description of how this measure is defined but academics and practitioners often define “risk premium” to be the “expected return in excess of a risk-free interest rate.” If this is indeed the GS ISG definition, then their reported Sharpe Ratio for bitcoin of 0.02 approximately follows from a risk premium of 1.9% and a volatility estimate of 93%. An appropriate question would be how and why an asset that has realized an average annualized return of 69% over the full sample would be “haircutted” down to a risk premium estimate of 1.9% and a Sharpe Ratio estimate of 0.02. Note that using the full sample data on bitcoin would result in a Sharpe Ratio of 1.0[6]. Using the average historical return for risk premium but the GS ISG measure of volatility would only reduce the Sharpe Ratio to 0.73. The piece also provides no information on how the standard errors are calculated.

To be clear, we recognize that it may be inappropriate and, in fact, dangerous to rely too heavily on historical data in deriving expected return or risk premium estimates to be used as inputs to asset allocation models. However, GS ISG presents the historical data in this section to be a motivation for a systematic asset allocation framework. We strongly argue that the piece should have contained more detail on why there is such disparity between the inputs used and the history.

- GS ISG uses the term “robust optimization model” and did report a wide uncertainty range around their estimates. Perhaps this is the key to why their optimization led to a zero allocation to bitcoin, despite high historical returns and low correlations to other assets. Widely discussed in the academic and practitioner literature, robust optimization techniques formally account for uncertainty around expected return and risk inputs[7]. Such techniques address the issue that certain statistics estimated from historical data may have an extremely high (or low) value but may also be subject to great uncertainty. Ignoring this uncertainty may lead to extreme allocations to such an asset which may not perform well “out of sample”. There are many robust methodologies – often differing by the degree of conservatism the modeler chooses – but a common outcome tends to be a down-weighting of the asset that is subject to more estimation error. Indeed, if this is the primary reason that the GS ISG optimization led to a zero weight on bitcoin vs. what would have resulted if they had used the historical data in a “non-robust” optimization, the authors should have identified that as the driver and given more detail on the specific technique they used. The 1.9% risk premium estimate still seems curious since most robust optimization techniques do not explicitly reduce the “point estimate” but instead utilize the uncertainty estimates to reduce the final solution. In addition, the authors are not explicit about what uncertainty has been assigned to estimates of other asset classes and how their risk premium estimates have been discounted to reflect their estimation errors.

- In fact, GS does not reveal any of the assumptions that are assigned to other asset classes or even what asset classes are considered. Clearly, the optimal allocation to bitcoin will depend on the expected return, risk, estimation uncertainty and correlations of other asset classes. Many of the valid criticisms of using historical data in an optimization framework around bitcoin are also applicable to every asset class, albeit perhaps to a lesser extent.

- GS ISG fails to report the assumed correlation of bitcoin with other asset classes, particularly with equity markets. Some investors who currently allocate to cryptocurrencies do so because of low correlations with traditional asset classes. As shown in Exhibit 19, GS ISG calculates that the correlation between bitcoin and the S&P 500 has been 0.05, suggesting that an allocation to bitcoin would have significant diversification benefits to a portfolio that is heavily weighted toward equity. The authors appropriately point out that this estimate has fluctuated quite a bit (ranging from -0.26 to 0.51[8]), so the diversification benefits may be somewhat muted at times. We would also note that, over its short history, bitcoin has demonstrated the undesirable tendency to be highly correlated with equities during extreme equity selloffs (e.g. – March 2020), certainly an unfavourable characteristic at a time when diversification is most desirable. Nevertheless, the generally low correlation should be attractive and result in an allocation to the asset unless the expected return is nearly zero or negative.

- Exhibit 18 shows that, according to the GS ISG model, bitcoin would need to have a return of 165% to yield a 1% allocation and a 365% return to yield a 2% allocation. Let’s ponder that result for a moment. GS is arguing that, if you expect an asset that is lowly correlated with equity to realize 160% return going forward, the model still would not even allocate 1%. Granted that a volatility of 93% is high but, with a 1% allocation and low correlation, the contribution to overall portfolio risk would be very low and likely acceptable. In addition, if you expect that bitcoin has a return of 350%, the GS model would not even allocate 2%. We find this to be striking and, frankly, preposterous. Relative to typical expected return estimates for traditional asset classes in the single digits or low teens annually, it simply defies logic that an allocator would not deploy a meaningful amount of capital to a lowly correlated asset with an expected return in excess of 160%. We believe that this claim suggests something is significantly flawed about their methodology and that the authors should have revealed a lot more detail in order to make such a bold claim.

Bitcoin in the SECOR Asset Allocation Model

At SECOR, we have developed a model that helps clients make strategic asset allocation decisions. Like the GS model, our model uses optimization techniques and does not rely solely on full sample historical data. In calibrating the inputs to the model, we also adjust our estimates to reflect data issues, estimation error and, from time to time, some “conditional” real time information, perhaps to incorporate research or a client view.

SECOR currently does not have a “house” view on bitcoin nor on cryptocurrencies broadly. Given the nascent state of the asset class and the compelling arguments from thoughtful investors for both the bear and bull cases, we are relatively agnostic on whether the assigned expected return on cryptocurrencies should be positive, negative or case specific.

With that caveat, we do think our framework could be helpful in conducting a quantitative analysis similar in structure to the model that GS ISG described in their piece and perhaps offer an alternative viewpoint to their strong conclusion that the allocation to cryptocurrencies should be zero.

The current standard SECOR model considers the following asset classes: Global Public Equity, US long duration Treasuries, US long duration Investment Grade and High Yield Credit, Emerging Market Debt, Hedge Funds, Private Equity and Private Real Estate. We then assign expected return, volatility and correlation assumptions to each asset class. The basis for these assumptions starts with the historical data but are adjusted to reflect data issues, assessments of the current market environment, uncertainty around forecasts and some intuition. Finally, the process imposes some constraints upon allowable solution weights to reflect practical issues such as: liquidity considerations, disallowing leverage and shorting at the asset class level and risk considerations that are not well captured in this framework.[9]

In assessing the potential allocation to cryptocurrencies[10], we perform a set of optimizations with the following calibrations:

- 70% volatility for bitcoin.

- A range of assumptions for expected return and correlations for bitcoin.

- A range of targeted portfolio volatilities (note that GS ISG never specified this parameter, but clearly the degree of risk aversion at the portfolio level matters in determining the appropriate allocation).

The results of this analysis are summarized as follows[11]: